Read Part 1 here.

Right from the very beginning, we were plagued with obstacles. The majority of which were the result of my dad’s profound stubbornness. He strongly believed he knew better than everyone—in all areas of life—including his oncology team. They took it in stride, as I’m sure they routinely faced these things. I, however, was completely chagrined. This would become one of the biggest lessons I’d learn in life.

He believed he could treat his cancer the way he treated having a cold or flu. It was expressed in no uncertain terms that he was to have a huge caloric intake as his body would need it. Sufficiently hydrating was also of the utmost importance. His unwillingness to do either of these things led to the traumatic events of his first day of chemotherapy.

The appointment itself went well. We left, excited for our burgers and shakes! Dad got into my car and suddenly stopped breathing. Even though I was only yards away from the emergency room when it occurred, the protocol—which remains wildly flabbergasting—required me to call 911 for help. In the time it took for the ambulance to show up (roughly 7 minutes, even though they were located a 2-minute jog from where we were), Dad had started, stopped, and started breathing again. We had a Peace Officer and 2 firefighters present when the paramedics arrived. Dad’s lips and face were still bluish/purple from the lack of oxygen. We joked that it was my shrill and desperate screams for help, reverberating off the concrete walls of the hospital parking garage, that kept him from crossing over that day.

I would also like to add that the ambulance cost us $260.

Dad refused to be admitted to the hospital and had to sign a waiver, but he did agree to be taken to his family doctor. With the help of the paramedics, we got him situated comfortably in my car and I took off to his doctor’s office—which was in a different city.

He was so dehydrated that the chemo overwhelmed his system, which did a number on his heart. It wasn’t a heart attack, but he was damn close to having one.

Did he learn his lesson?

No. Of course not.

To say his overall state nosedived from this point is like saying water is wet. Dad did what he wanted to do. The few times he followed the doctors’ advice, he made near-miraculous recoveries. That’s not hyperbole either—the difference was astounding.

I still vacillate between being furious with him and having radical acceptance. He suffered needlessly, and that was the most painful thing to watch. I felt helpless.

Dad, I feel like you’ve doused yourself in gasoline, and you’re on the verge of lighting the match because you think you are somehow fireproof. I’m so scared of that point of no return. That moment you say, “Oh shit, this was wrong, I want to go back.” and it will be too late to go back.

The truth was (and remains) that I was ok if he didn’t want to fight the cancer. I understood. It’s an incredibly hard thing to do. I didn’t want to lose my dad. I’m choking on sobs as I type this. It was a devastating loss, and the thought of it rocked me to my core, but more than anything—I didn’t want him to suffer. He was caught in a space of not wanting to fight and not wanting to die. That’s a godawful place to be.

I tried my damnedest to make his time as worthwhile as possible. By his third round of chemo, we needed a wheelchair to get him to and from his appointments. At the end of an appointment, when the hall to the exit was clear, I’d take off in a sprint, pretending I was busting Dad out of the hospital. He gleefully giggled as I prayed I wouldn’t trip over my own feet and eat shit.

We’d erupt through the automatic doors! If there was barely any traffic, I’d sprint the short distance down the road and make the sharp left-hand turn into the parking garage exit ramp. It wasn’t a steep incline, but enough to feel it. I’d swerve the wheelchair around the speedbumps and beeline to the car. I’d be out of breath and laughing by the time we stopped. Dad would have a huge grin on his face. He used his iPhone to track how fast we were going and I’d get a, “Not bad, kid!” as we pulled away from the hospital.

The other times, when he had been especially difficult: instead of the exit ramp—I would use the automatic doors to the parking garage. They had a raised metal something-or-other on the ground that took a good deal of force to get the wheelchair over. It was uncomfortable for Dad to be aggressively shoved over that bump. He’d see me running toward the doors and say, “Hey, hey, easy! Easy!” white-knuckling the wheelchair, followed by “YOU DID THAT ON PURPOSE!”

“Yes. Yes, I did. I’m glad you’re catching on.”

“Damn brat kid,” he’d grumble

I was 37 years old and he was 64.

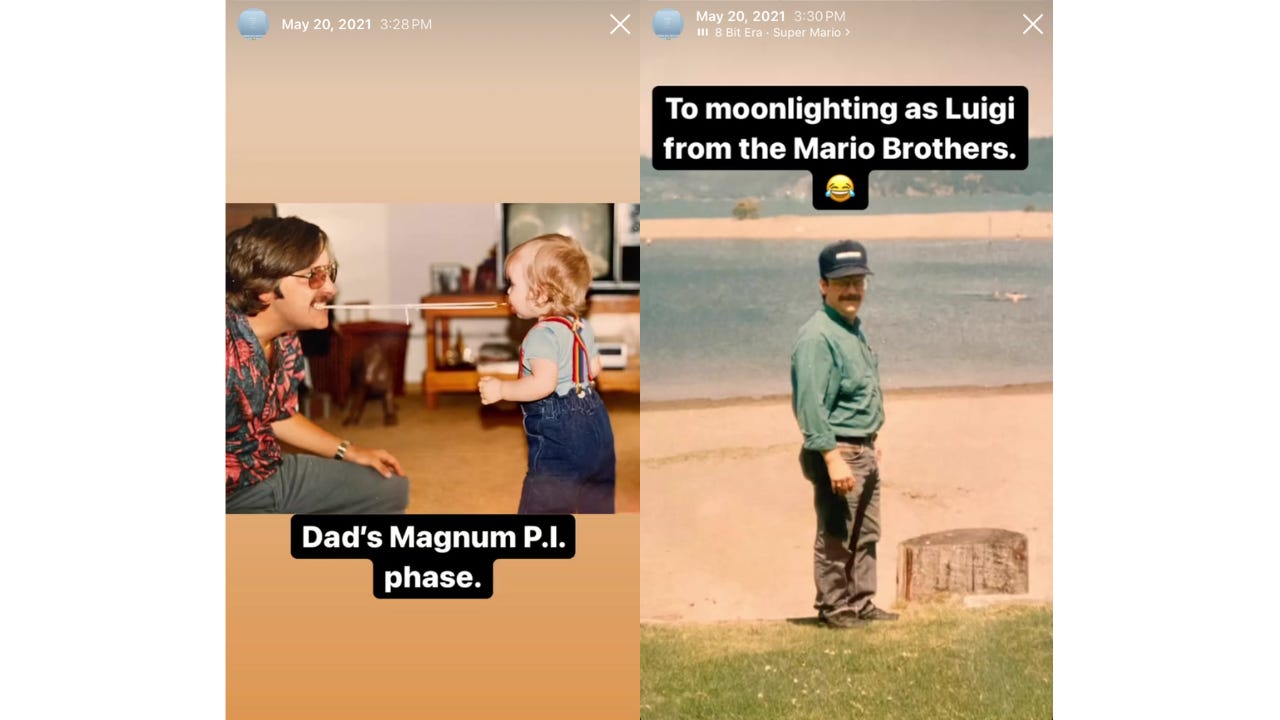

Another favourite tactic of mine was making fun of him on social media:

I sat next to him as I posted this.

“Ass-ah-hole” he said in a sing-song voice, laughing while punching me in the arm. “Send that to me.”

So I did. Every now and again, I’d catch him looking and laughing at these photos. He’d turn around and say “Damn brat kid!”

“Love you too, dad.”

I’m so sorry that you had similar experiences with your dad. And for your loss.

I suspect a lot of people are in that limbo— whether facing an illness or not. This world is becoming increasingly more difficult to exist in, and I think a lot of people are incredibly tired. Having glimmers helps… even when you know the outcome isn’t going to be what you want… to have your life sprinkled with little bits of joy makes it more palatable.

Thank you for this lovely comment, Kevin. ☺️

Ah man, ah man, nothing to say