The Gruesome Twosome (Part 1)

Exactly three years ago today (as of writing), my dad and I sat in the thoracic surgeon's office, learning he had stage 4 cancer. I don’t think I’ll ever forget that day, though I wish I could.

We were already privy to the fact he had cancer, just not the stage nor his prognosis. We opted out of receiving his timeline and to the shock of many, he died 5 months later.

His brief battle was riddled with horrific moments. A couple that I touch on in In A Flash. It all happened during the pandemic—the healthcare system and hospitals were so overburdened—that not only did we slip through the cracks, but in the end, they decided to let him die. This provincial government instituted a system whereby the hospitals ultimately had to choose who would live or die—and my dad didn’t make the cut.

Let me back things up slightly…

In the summer of 2020, my dad and I found ourselves in similar situations: my mother got involved in an online love scam and divorced my dad. My 13-year relationship also ended with my common-law husband cheating. We were both crushed by our circumstances. Dad’s mental health tanked, and there was genuine concern about what would happen if he was left alone. Since we found ourselves in similar situations (and dad was suicidal), I moved back in with him, hoping we could help each other get back on our feet. Little did we know that just a few short months later, we would receive his devastating diagnosis.

He had esophageal cancer that spread to his liver and lymph nodes. The tumour in his esophagus was roughly the size of a grape—located just above the opening of his stomach. He was referred to the thoracic surgeon to see if that tumour could be surgically removed. Leading up to that appointment, Dad insisted:

“All they have to do is remove the parent cancer, and the rest dies.”

“Dad, it’s cancer, not vampires. Have you been watching The Lost Boys again?”

Unfortunately, surgery wasn’t an option, and he began chemotherapy. His very first treatment landed on my birthday. Dad was upset about it, but I couldn’t have asked for a better gift:

“What better gift than to start fighting this cancer?!”

“That’s not how we want to spend your birthday. In the hospital. I can see if they can change it.”

“NO! What if it means starting treatment later, not sooner? Seriously, Dad, it’s ok. I’ll tell you what… we’ll go for your treatment and then we can stop at the drive-in, and grab some burgers and shakes to celebrate your first round and my birthday.”

He scrunched his face up.

“Raspberry milkshake, double cheeseburger and onion rings, Pops,” I said nudging him with my elbow. “You’re supposed to eat a lot anyway, this is perfect!”

He hissed at me, as he often did when he disapproved of something but couldn’t be bothered to use his words.

“Love ya too, ya little shit,” I laughed in response.

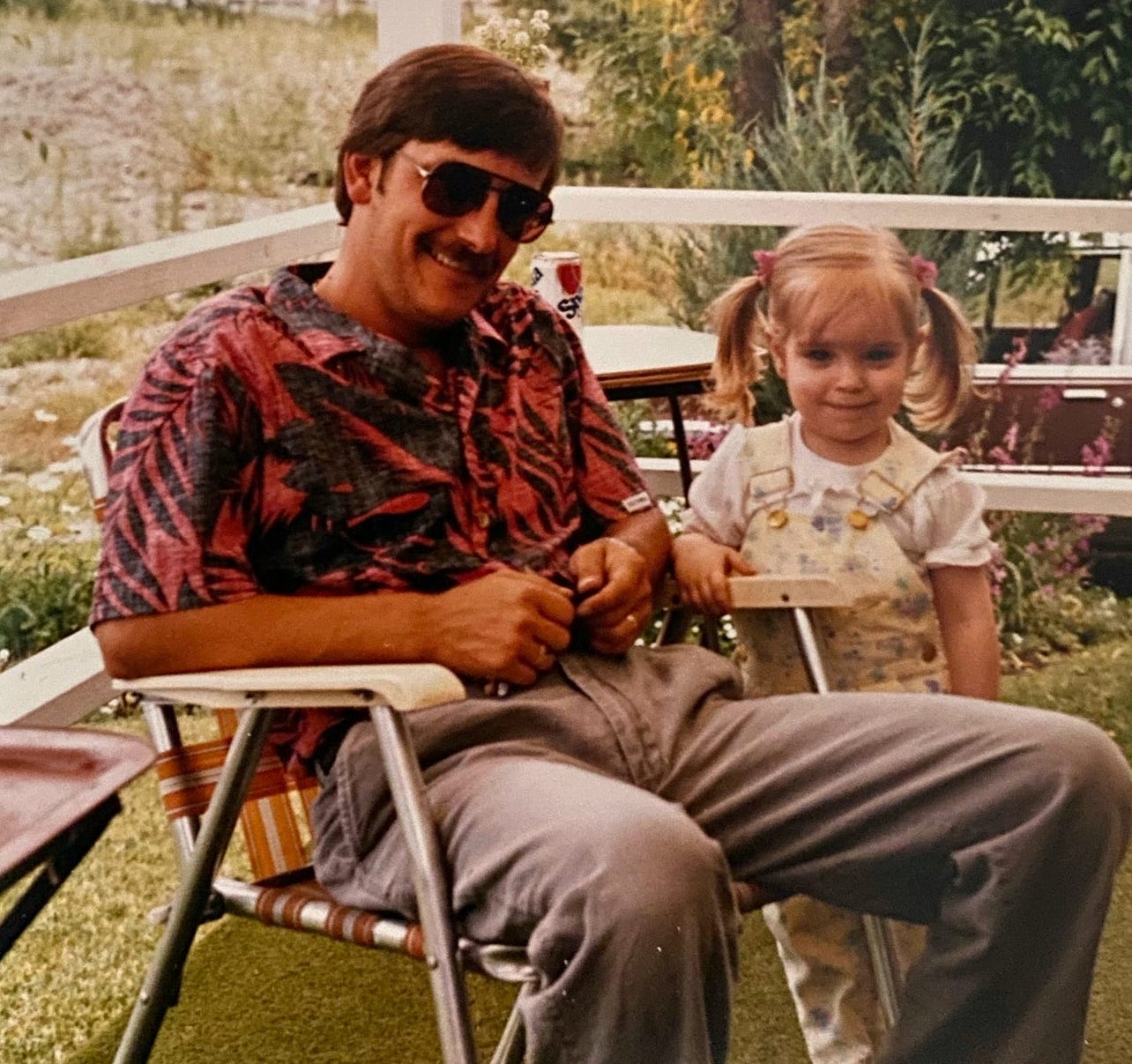

I suppose it would help you to know that my dad and I had more of a sibling relationship than father/daughter. He was like a much older brother—more than a father figure. Our relationship was often contentious and complicated. Without getting into it all, I will say I love my dad a lot and will also probably spend my life working through a world of hurt.

Agreeing to be my dad’s caregiver was a no-brainer, which is hilarious to say as someone with an incurable, complex neurological disease. I go into more detail about that here, but what you need to understand is that I was very ill at the time.

I was incredibly concerned about what we would do when the severe migraines or cluster headaches hit. Dad and I were on our own. To paint a picture of how bad things could get:

I once walked into the living room, in blinding pain. The room was spinning and I was violently ill. I needed Dad to do more for himself—he was still capable of it—at that point. Before I could say anything, he said, “Gah! You look like shit!” His first round of chemo damn near killed him, and he wasn’t lookin’ so hot either.

“High praise coming from a hobgoblin,” I said, trying not to dry heave as I covered my eyes. (in a bid to stop the light from causing a piercing pain in my brain.)

He hissed at me—again.

At his appointments, we’d watch the medical staff read his chart over and over again because looking at us, it wasn’t clear who had cancer. In fact, there were several days he looked a lot better than I did. We watched the wheels turn in the nurses’ heads as if they were thinking, “She doesn’t look like an Oscar…” or questioning whether they had accidentally grabbed the wrong chart.

On really bad days, one of us would get the other one dry heaving, and it would be a grotesque symphony of retching and laughter. We were a fucking mess. The worst was when we were trapped in the car with one another, unable to escape the perpetual aggravation of nausea and vomiting. As much as we cried together, we cried from laughter almost as often.

One time, Dad almost made us both faint. An unfortunate side effect of his chemo was patches of his skin became necrotic. It left awful gaping wounds on his arms that needed to be dressed. Dad was notoriously terrible with these things. There were enough tales of all the times he fainted when things got a bit gory. That said—I’ve fainted too, but it’s once I’ve thought about it or processed what I’ve just seen. It’s odd because it’s like my brain has an autopilot function specifically for these types of things. And with that, I can tend to some really awful situations and wounds and be fine, until after. Then I’ll faint. Or, if that autopilot fails to activate—it’s lights out right away.

I was dressing a particularly gnarly wound:

“Hey, kid,” Dad said in a tone that snapped me out of autopilot. “I’m feeling a bit woozy.”

Oh no.

“OK, can you bring your head to your knees?”

I sat on the floor—at his feet as he brought his head to his knees. I started to breathe deeply because I suddenly felt awfully woozy too. I wrapped my arm around his legs, brought my knees up and put my head down. I leaned into him—so the top of his head was very near the side of mine. If he were to pass out and fall off the chair, I was there to stop him from hitting the ground.

“Uh, Sar? You don’t look so good,” he said as he peeked up at me.

“I am my father’s daughter, what can I say.”

We were both the most ungodly shades of pale and I once again found myself hysterically laughing at the state of us. One of the superb gifts of dissociation, I suppose—is being removed from oneself to view the situation from the outside.

“Who’s the bozo that left us in charge, huh?” I asked my dad as we both breathed through the looming threat of a fainting spell.

To be continued…

This is so hard to read, and yet I, also, found myself smiling. I was my sister's advocate when she was battling cancer that finally took her in 2004. I look back, and through the horrific pain and what she suffered, there are also memories wrapped in laughter and unexpected humor, such precious, precious gifts, late night sharing, and deep intimacy of our hearts.

Her death really messed me up, and I'm not sure I'll ever really heal from it. But I am so very grateful for the memories we created and shared together, particularly, in her last year of life. Your story touches me there, in that most tender place in my heart. Thank you for sharing it, Sarah. I am so deeply honored for the privilege of being able to witness it. Enveloping you with tender love ❤️

Your story is like punch in the gut and a circus at the same time. Thank you needed that 💩 🍦 to keep going 😆 I'm sorry for your loss.